If stablecoins really work, they will be truly disruptive

Reposted original title: “The Economist: If Stablecoins Are Truly Useful, They’ll Also Be Deeply Disruptive”

One thing is clear: the belief that cryptocurrencies have yet to deliver any significant innovation is now outdated.

Conservative Wall Street professionals often discuss crypto “use cases” with a mocking undertone. Experienced professionals are familiar with similar trends. Digital assets come and go, often capturing the spotlight and generating excitement among memecoin and NFT enthusiasts. Beyond speculation and serving as tools in financial crime, their practical utility has frequently been found lacking.

But this latest surge is different.

On July 18, President Donald Trump signed the Stablecoin Act (GENIUS Act), granting the regulatory clarity for stablecoins—crypto tokens backed by traditional assets, typically US dollars—that industry insiders have long sought. The sector is in a growth phase, and Wall Street professionals are now racing to participate. “Tokenization” is also gaining momentum, with on-chain asset volumes climbing sharply—covering stocks, money market funds, and even private equity and debt.

Innovators are enthusiastic, while established institutions express concern.

Robinhood CEO Vlad Tenev claims this technology could “lay the foundation for crypto to become a pillar of the global financial system.” European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde sees things differently, warning that the rise of stablecoins amounts to the “privatization of money.”

Both camps recognize the scale of the transformation underway. Mainstream markets now face a more disruptive change than early crypto speculation. Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies promised to be digital gold, while tokens simply serve as wrappers or vehicles for other assets. That may sound unremarkable, but some of the most transformative innovations in modern finance—like exchange-traded funds (ETFs), Eurodollars, and securitized debt—have all changed how assets are bundled, divided, and restructured.

There are currently $263 billion worth of stablecoins in circulation, up about 60% from a year ago. Standard Chartered expects the market will reach $2 trillion within three years.

Last month, JPMorgan Chase—the largest bank in the United States—announced plans to launch a stablecoin-like product called JPMorgan Deposit Token (JPMD), despite longstanding skepticism toward crypto from CEO Jamie Dimon.

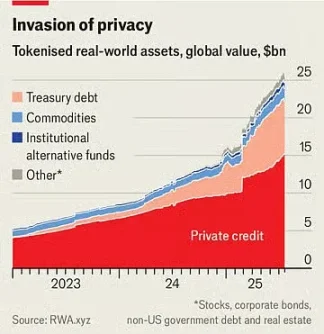

The market value of tokenized assets is just $25 billion, but it has more than doubled over the past year. On June 30, Robinhood released more than 200 new tokens for European investors, enabling them to trade US stocks and ETFs outside regular market hours.

Stablecoins dramatically lower transaction costs and enable near-instant settlements since ownership is immediately recorded on a blockchain, cutting out intermediaries that run traditional payment rails. This is particularly valuable for cross-border transactions, which are currently costly and slow.

Although stablecoins make up less than 1% of global financial transactions today, the GENIUS Act is set to boost their growth. The law clarifies that stablecoins are not securities and mandates they be fully backed by safe, liquid assets.

It’s reported that retail giants such as Amazon and Walmart are said to be considering launching their own stablecoins. For consumers, these stablecoins could function similarly to gift cards, providing balances for spending with the retailer—possibly at a lower cost. This could disrupt companies like Mastercard and Visa, which earn about a 2% fee on US sales they process.

Tokenized assets are digital representations of other assets, such as funds, corporate shares, or baskets of commodities. Like stablecoins, they can speed up and streamline financial transactions, especially for illiquid assets. Some products are more hype than substance. Why tokenize stocks? Perhaps to enable around-the-clock trading, since traditional stock exchanges don’t need to be open, but the benefits are questionable. For many retail investors, marginal trading costs are already very low or even zero.

The Push for Tokenization

Still, many products are less flashy.

Take money market funds, which invest in Treasury bills; tokenized versions can double as payment instruments. Like stablecoins, they’re backed by safe assets and can be exchanged seamlessly on blockchains. They also offer higher yields than banks: the average US savings account pays less than 0.6%, while many money market funds yield as much as 4%. BlackRock’s largest tokenized money market fund now has a value exceeding $2 billion.

“I expect that, one day, tokenized funds will be as familiar to investors as ETFs,” CEO Larry Fink wrote in a recent letter to shareholders.

This has the potential to disrupt established financial institutions.

Banks may be trying to break into these new forms of digital asset structuring, but in part, they’re motivated by recognizing the threat tokens pose. The combination of stablecoins and tokenized money market funds could ultimately make traditional bank deposits less attractive.

The American Bankers Association notes that if banks lose around 10% of their $19 trillion in retail deposits—their lowest-cost funding—their average funding costs would rise from 2.03% to 2.27%. While total deposits (including business accounts) wouldn’t decline, bank margins would be squeezed.

These new assets could also disrupt the wider financial system.

For instance, holders of Robinhood’s new stock tokens do not actually own the underlying shares. Technically, they hold a derivative that tracks the asset’s value—including any dividends—but not the shares themselves. This means missing out on the voting rights stock ownership confers. If the token issuer goes bankrupt, holders may have to compete with other creditors for the underlying assets. Earlier this month, fintech startup Linqto—which issued private company shares via special-purpose vehicles—filed for bankruptcy. Buyers are now unsure whether they truly own the assets they thought they had.

This marks one of the biggest opportunities of tokenization, but also one of the greatest regulatory challenges. Tokenizing illiquid private assets creates new markets for millions of retail investors, opening previously closed doors to trillions of investable dollars. It means everyday investors can now buy stakes in some of the most exciting private companies—assets that were once out of reach.

This raises important regulatory questions.

Regulators like the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) have far more authority over public companies than private ones, which is precisely why public equities are considered suitable for retail investors. Tokens representing private shares can effectively turn once-private equity into assets that trade as easily as ETFs. But while ETF issuers commit to providing intraday liquidity by buying and selling underlying assets, token providers do not. At sufficient scale, tokens could make private companies functionally public, without any of the standard disclosure requirements.

Even crypto-friendly regulators want clear boundaries.

SEC Commissioner Hester Peirce—often called “Crypto Mom” for her pro-crypto stance—emphasized in a July 9 disclaimer that tokens shouldn’t be used to skirt securities laws. “Tokenized securities are still securities,” she wrote. That means, regardless of their form, companies issuing securities must comply with disclosure rules. While this sounds fair in principle, the flood of new, structurally novel assets will keep regulators in a perpetual race to catch up.

This paradox remains unresolved.

If stablecoins are truly useful, they will also be deeply disruptive. The more attractive tokenized assets become to brokers, clients, investors, merchants, and financial firms, the more fundamentally they can change the financial landscape—an evolution that’s both exciting and unsettling. Whatever the outcome, one thing is clear: the belief that cryptocurrencies have yet to deliver any significant innovation is now outdated.

Disclaimer:

- This article is reprinted from [TechFlow] under the original title, “The Economist: If Stablecoins Are Truly Useful, They’ll Also Be Deeply Disruptive.” Copyright remains with the original author [The Economist]. If you have concerns about this reprint, please contact the Gate Learn team. We will address any disputes promptly according to our established procedures.

- Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author alone and do not constitute investment advice.

- The Gate Learn team provides translations in other languages. Unless Gate is expressly mentioned, translated articles may not be copied, distributed, or plagiarized.

Share